Festival Theaterformen 2018 "Watch & Write" - Ismael Fayed on "Saigon" by Caroline Guiela Nguyen and Les Hommes Approximatifs

Braunschweig, 11. Juni 2018

Colonialism Sweet and Sour

by Ismael Fayed

In Feburary 2017, then presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron, apologized for his comments on French colonialism in Algeria. During a previous trip to Algeria, Macron had called French colonization a "crime against humanity" – a term that proved controversial amongst many back home. Macron did not apologize to an Algerian audience, nor did he apologize for the devastating effects of French colonialism (which lasted 132 years) on Algeria. He apologized to the French people of the city of Toulon saying, "I am sorry to have offended you, to have hurt you". Yes, French people were hurt by being confronted with the bloody, horrible past of colonialism. Perhaps this is the fragility of the colonizer.

In June 2017, Caroline Guiela Nguyen from the theater company Les Hommes Approximatifs premiered her show, "Saigon" at the Festival Ambivalence(s) in France, a little further north from the city of Toulon. Perhaps continuing a theme from her previous production Mon Grand Amour (2016), this production is switching back and forth between Paris and Saigon over four decades, starting from the end of the French occupation of Vietnam (consolidated as a French protectorate by the 1887) in 1956 all the way to 1996 when the Vietnamese government allowed Vietnamese expatriates, the Viet Kieu, the right to return.

A restaurant as a place where public and private converges

In three hours, over the course of three parts or chapters (Departures, Exiled and Return) and with a cast of a dozen or more characters, Nguyen stages multiple narratives and stories in the setting of a restaurant, colorfully called ‘Saigon’ in its Paris iteration, run by a Vietnamese emigrant, Mary Antoinette and her niece Lam. It is through the microcosm of Mary’s restaurant and her story that the other narratives of the patrons are told.

Inside the Restaurant "Saigon" © Jean-Louis FernandezIn a highly naturalistic, almost cinematic scenography of a real restaurant, with a kitchen, utensils, tables and chairs, and outstanding light design, we get to hear the voice-over of Lam, soft, young and timeless relating the story of her aunt and how it overlaps with all who come to her restaurant. Nguyen even pays homage to the pervasive culture of karaoke in East Asia and has a corner with a mic and a keyboard where music and singing are integral parts of the visual and soundtrack of the play (giving the play a real sense of melodrama-- as a “melody-drama”).

Inside the Restaurant "Saigon" © Jean-Louis FernandezIn a highly naturalistic, almost cinematic scenography of a real restaurant, with a kitchen, utensils, tables and chairs, and outstanding light design, we get to hear the voice-over of Lam, soft, young and timeless relating the story of her aunt and how it overlaps with all who come to her restaurant. Nguyen even pays homage to the pervasive culture of karaoke in East Asia and has a corner with a mic and a keyboard where music and singing are integral parts of the visual and soundtrack of the play (giving the play a real sense of melodrama-- as a “melody-drama”).

This choice of setting, namely a restaurant, cleverly sets a sense of domesticity but also gives the possibility of an audience. It becomes the point where the public and private converge, and what could be more domestic and intimate than cooking and serving one’s own cuisine? Yet the serving part also problematizes that notion of the choices one has. One can imagine that Mary had very few skills when she came to France (she speaks broken French, is illiterate and probably was a peasant back in Vietnam) and “cooking” and “serving” the French must have seemed one of the few possible options to survive.

Women are the ones bearing the costs of war

In showing this domestic scene Nguyen (who was awarded 2019 the Jürgen Bansemer & Ute Nyssen Dramatikerpreis) does something remarkable: She introduces the idea that the feminine, the domestic, needs not to be invisible, irrelevant, when examining a history. Women are always the ones bearing the costs of cataclysmic changes like war, and yet their stories are not often told. When one thinks of war, one thinks of weapons, tanks, bombs and territory gained and resources lost, one never thinks of who survived and how. Very little is told to us about what happens after the bombing or after the last solider departs. Nguyen tells us what soldiers do and what they leave when they depart: a trail of blood and tears.

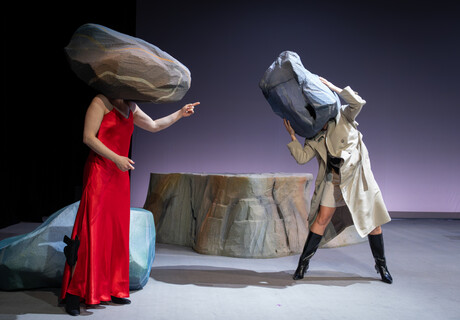

Wedding without wedding-guests © Jean-Louis Fernandez

Wedding without wedding-guests © Jean-Louis Fernandez

Speaking of blood and tears: there's a lot of the latter. Nguyen does not spare anyone the harrowing realities of colonialism. In performances awash with pathos and tragedy, nearly all the characters at some point break down in tears, some more hysterically than others, some out of Post Traumatic Stress disorder (Edouard, the solider fighting in the French army), some out of their complicity in the looting and destruction of Vietnamese communities and resources (Meme Gautier whose husband employed Vietnamese young men, some of whom ended up being “missing in action” during WWI and WWII) to not-very-convincing biracial children (Antoine, Edouard’s son (played by a “white” actor, whose curt Vietnamese mother, never shies away from throwing a few punches, rendering her difference, and her son’s alienation from that difference, a source of constant misery).

Complex love stories between colonizers and colonized

There is an intricate web of love stories between Vietnamese and French women and men, colonizer and colonized. On the one hand, there is the love of the colonized for their colonizers that can be seen as seeking respect and recognition. One the other hand, there are colonizers who fetishize the colonized as the subject of their own guilt. Saigon becomes an imagined space where all these conflicted narratives unfold, using a dramaturgy of memory, that follows no strict chronology: the past, the present and the future can all be converged into one moment creating a density of experience that might be the perfect conduit to an experience as conflicting and problematic as colonialism and its history.

Karaoke-Misery © Jean-Louis Fernandez

Karaoke-Misery © Jean-Louis Fernandez

As an Arabic-speaking spectator not entirely familiar with the complex and tragic history of modern Vietnam – French colonialisation of Vietnam (1887-1954), two civil wars (First Indochina War 1946-1954 and the Second Indochina War 1955-1975), American War (1954-1975), Vietnamese occupation of Laos (1959-1975) and Cambodia (1975-1989) – sitting there trying to decipher the French dialogue intermixed with Vietnamese with subtitles in English and German projected on top of the stage, created a cacophony of linguistic layers that sometimes was as exhausting as it was distracting. It also created a sense of incomprehensibility or rather what gets lost as one moves from one language to the other, the other language being the language of the colonizer or the oppressor. And in some cases, even the language of the lover. Whether by speaking or by singing or by reading the subtitles, Nguyen’s heavily textual staging leaves little doubt about the overwhelming sense of loss one keenly feels outside of one’s mother-tongue. Adding to that a general sense of displacement and alienation.

It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, the metaphor of the kitchen, cooking and the history of a certain cuisine with its very particular flavours and recipes-- as if somehow the bitterness, acrid taste of realization of the present, is contrasted with the almost cloying sweetness of nostalgia and the melancholy of remembrance. Perhaps there is even a little saltiness of being aware that no love stories will rectify the devastation of the past without confronting, speaking about it and perhaps even staging it as Nguyen did – but maybe with a less sickly sweet palate.

Ismael Fayed is an independent writer and researcher based in Cairo. He has been writing and researching contemporary artistic and cultural practices of the Middle East since 2007. His focus is on visual arts and film. He has contributed to local and international publications, including MoMA's upcoming volume on Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents. His writings appeared in Mada Masr, Muftah, Nafas Art Magazine, ArteEast, Aperture and many others.

Ismael Fayed is an independent writer and researcher based in Cairo. He has been writing and researching contemporary artistic and cultural practices of the Middle East since 2007. His focus is on visual arts and film. He has contributed to local and international publications, including MoMA's upcoming volume on Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents. His writings appeared in Mada Masr, Muftah, Nafas Art Magazine, ArteEast, Aperture and many others.

Hier die deutsche Übersetzung dieses Artikels.

Here Milisuthando Bongela writes about the situation of cultural journalism on the African continent. And here Yvon Edoumou on the question whether "poor" people can enjoy arts. Stéphanie Dongmo portraits the theatre director Martin Ambara from Cameroon (in German). Enos Nyamor writes about the Kenyan Theatre today.

This text is a product of "Theaterformen" festival's journalistic project "Watch & Write" and is being published on nachtkritik.de in the context of a media cooperation with the festival. It is not part of the regular programme on nachtkritik.de.

Schön, dass Sie diesen Text gelesen haben

Unsere Kritiken sind für alle kostenlos. Aber Theaterkritik kostet Geld. Unterstützen Sie uns mit Ihrem Beitrag, damit wir weiter für Sie schreiben können.

mehr nachtkritiken

meldungen >

- 15. April 2024 Würzburger Intendant Markus Trabusch geht

- 15. April 2024 Französischer Kulturorden für Elfriede Jelinek

- 13. April 2024 Braunschweig: Das LOT-Theater stellt Betrieb ein

- 13. April 2024 Theater Hagen: Neuer Intendant ernannt

- 12. April 2024 Landesbühnentage laufen 2024 erstmals dezentral

- 12. April 2024 Neuauflage der Demokratie-Initiative "Die Vielen"

- 12. April 2024 Schauspieler Eckart Dux gestorben

- 12. April 2024 Karlsruhe: Graf-Hauber wird Kaufmännischer Intendant

neueste kommentare >