Festival Theaterformen 2018 "Watch & Write" – Carla Lever on Cape Town theatres that are challenging South Africa's cultural post-Apartheid segregation

June 14th, 2018

Taking Part: Callenging cultural segregation in Cape Town

by Carla Lever

If you're interested in the dramatic, Cape Town is for you. Teeming with artistic talent, it's a city built between mountain and sea, built on a jut of peninsula piercing two oceans. Forget for a moment those talented actors: Cape Town herself makes quite the entrance.

The Cape Town most curious theatregoers will explore is clustered within a small ten kilometre radius of the city centre, a delightful area dotted with transport links and coffee shops, boutique stores and colourful urban street art. If you can take your eyes away from the city's staging, though, its underlying structural narrative tells a far less beautiful tale.

This is because the Cape Town most tourists will not see is one of far-flung suburbs – sandy stretches prone to flooding, unlit corrugated shacks, stretches of dune and shrub, communal toilets and pirated electricity lines. To explore deeper in Cape Town, then, is to traverse a chequered racist history of design interventions: its structural bones, like most South African cities, are Apartheid-designed. Obstacles preventing people from a better-placed life are almost comically strewn – extra wide freeways so people can't cross on foot, strategically placed golf courses and train lines buffering wealthy white suburbs from poor black ones, public transport that conveniently stops at the outskirts of the city centre.

In a country where Apartheid's legacy means that race almost inevitably determines economic class, gentrification means Cape Town may be a rapidly changing city, but it is still fundamentally an unequal one. Legislation may no longer prohibit people from living where they want, but economic reality still does – arguably even more effectively.

Centrestage Politics

It is hardly surprising, then, that theatre – at least the kind that jumps to western mind – remains a predominantly white industry in South Africa. It makes sense: being an artist is a luxury available to few without additional economic support, while being an audience member requires enough disposable income for luxuries like entertainment.

While theatre in Cape Town is exciting and talent diverse, prime roles and awards still go to established white actors and directors, playing in middle class suburbs to audiences that are just as white. Though a generalisation, it is fair to say that when black actors play in large city theatres, it is rarely in works of their own making and direction, but rather telling the stories of white playwrights and directors.

It's against this backdrop that small, independent venues willing to subsidise risk-taking artists are really making a difference. Spaces like the Alexander Bar – a cosy 42-seater black box theatre in the bustling centre of Cape Town nightlife – really make their mark on a scene that's struggling to diversify. Conveniently perched on top of the bar that ensures its financial viability, the theatre offers artists a well-marketed platform for new work on a profit share model. Taking away the need for steep deposits and rental unlikely to be recouped in ticket sales means a vital barrier to entry has been taken down for theatremakers.

Theatre makers, not gatekeepers

"I hate the idea of gatekeepers in culture – that only few people have the ability to give a wide platform to new voices," explains venue-manager Jon Keevy, himself an award-winning producer and playwright. "I think that having a platform gives you a responsibility to take risks. Institutions have power to control access to training and opportunities and so far in South Africa many have used it poorly when it comes to transformation. I have a theatre now and I'm not turning away anyone who is passionate about working in this crazy field. I never want to be a gatekeeper."

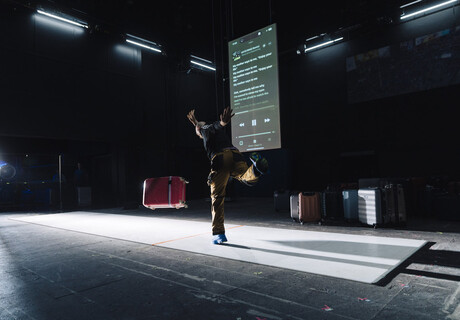

"The Champion", one of the shows at the Alexander Bar © Nardus Engelbrecht

"The Champion", one of the shows at the Alexander Bar © Nardus Engelbrecht

Alexander Bar help other small venues thrive too. They have pioneered the Open Theatre Toolkit: software that drastically lowers the amount of time and money it costs to run a venue by managing an operation on one platform. Despite these initiatives, Keevy has been frustrated by mainstream Capetonian audiences' reluctance to embrace diverse theatre outside of the regular – predominantly white – art scene. Whether he programmes highly regarded touring acts from the rest of the continent or rising local stars, if the work is by unknown black performers, audiences uniformly tend to stay away. His frustration is palpable. "Local artists are hesitant to put on work with us when they know from experience that audiences in the city will be small. And they're right. They don't get the support they need and audiences are missing out because they want to play it safe by seeing work by known artists who are typically white."

"Shack theatre" in an informal settlement

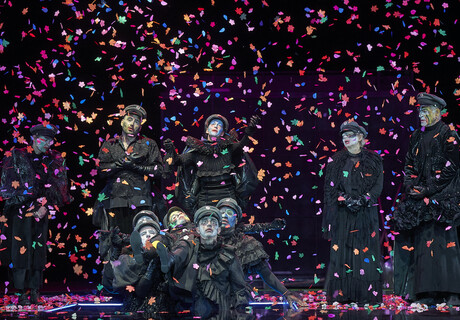

Fortunately, the rest of the city is not waiting for middle class Capetonians to change their cultural tastes. Situated thirty kilometers from Alexander Bar, in the sprawling informal settlement of Khayelitsha, the newly built Makukhanye Art Room bills itself as offering South Africa's first "shack theatre" catering to an "ever-growing audience and network who find it difficult to access the cultural infrastructure that otherwise exists in Cape Town's city center."

Khayelitsha is home to two and a half million Capetonians, but is still treated in many ways by government as a temporary housing solution, with the bare bones of public services, formal transport routes and infrastructure servicing around two thirds as many people as live in the formal city of Cape Town itself. The self-built Makukhanye Art Room is home to Theatre 4 Change, a group of activists and artists bent on claiming a centre for cultural production that no longer requires artists and audiences to commute long and dangerous routes away from their own neighbourhoods.

Makukhanye Art Room © David Harrison

Makukhanye Art Room © David Harrison

Venue founder Mandisi Sindo comments that "there are a lot of politics around theatre – that's the reason why there is mainstream theatre in town and there is community theatre which is practiced by black people in the townships. And that is even set in the university level where there's acting for theatre and television, then separately there is community theatre, designed basically for black people."

"Black artists don't really get a platform, especially black directors," he notes. "That was one of the reasons we had to make a theatre in the townships. Also, if one of us has a production at eight o clock in the evening in town, none of our people will be able to travel to a big theatre to see it. It's a disadvantage to getting work in big theatres, and we don't even get invitations to do so!"

Theatre in the backyard of a township

Theatre in the Backyard is another company challenging spatial segregation in the Cape Town art scene. They deliver precisely what their name suggests: a show presented in a carefully-selected back yard of a township resident. Community theatre group Ikhwelo Arts have partnered with a local tour operator to bus people into the township Langa from central Cape Town, present a tight thirty minute show and, afterwards, invite the audience inside the home for beer and a home-cooked dinner. "I'm using people's back yards," says Director and producer Mhlanguli George, "and each and every yard has a story to tell – stories that are very close to life."

Are these initiatives working? Some days, to tired theatremakers and frustrated venue operators, it may seem not. However, look at the results. In early July, Theatre in the Backyard will take two works hundreds of kilometers up country to the prestigious National Arts Festival in Grahamstown. "The Champion", a play produced and initially presented at Makukhanye Art Room, in Khayelitsha informal settlement, enjoyed a two week run at Alexander Bar to excellent reviews and strong attendance. Its actor, Khayalethu Anthony, also won Cape Town's most prestigious mainstream award for best performance in a one-man show, an extraordinary achievement for a performance that may otherwise never have been seen by the judges. Conversely, "Selwyn and Gabriel" – a new local text that already enjoyed two hit runs at the Alexander Bar – is scheduled to play at the Makukhanye Art Room. The walls are coming down: actors are working, and work surely is moving. Change, then, may not be center stage on Cape Town, but it is everywhere in the wings.

Carla Lever (South Africa) has done her PhD in performance studies and researched south african national identity. She works as theatre critic, cultural journalist and lecturer.

Carla Lever (South Africa) has done her PhD in performance studies and researched south african national identity. She works as theatre critic, cultural journalist and lecturer.

Hier findet sich die deutsche Übersetzung des Artikels.

Here Milisuthando Bongela writes about the situation of cultural journalism on the African continent. Yvon Edoumou questions whether art in Kinshasa is accessible for "poor" people. Stéphanie Dongmo portraits the theatre director Martin Ambara from Cameroon (in German). Ismael Fayed writes about the production "Saigon" by Caroline Guiela Nguyen and Les Hommes Approximatifs. Enos Nyamor reports on Kenyan theatre today, Aboubacar Demba Cissokho covers theatre in Senegal (in German).

This text is a product of "Theaterformen" festival's journalistic project "Watch & Write" and is being published on nachtkritik.de in the context of a media cooperation with the festival. It is not part of the regular programme on nachtkritik.de.

Schön, dass Sie diesen Text gelesen haben

Unsere Kritiken sind für alle kostenlos. Aber Theaterkritik kostet Geld. Unterstützen Sie uns mit Ihrem Beitrag, damit wir weiter für Sie schreiben können.

mehr nachtkritiken

meldungen >

- 22. April 2024 Intendanz-Trio leitet ab 2025 das Nationaltheater Weimar

- 22. April 2024 Jens Harzer wechselt 2025 nach Berlin

- 21. April 2024 Grabbe-Förderpreis an Henriette Seier

- 17. April 2024 Autor und Regisseur René Pollesch in Berlin beigesetzt

- 17. April 2024 London: Die Sieger der Olivier Awards 2024

- 17. April 2024 Dresden: Mäzen Bernhard von Loeffelholz verstorben

- 15. April 2024 Würzburg: Intendant Markus Trabusch geht

- 15. April 2024 Französischer Kulturorden für Elfriede Jelinek

neueste kommentare >