Great Britain's immersive theatre scene, going strong in pandemic times

No show without an audience

by Alice Saville

August/December 2020. As the UK's theatres closed, they offered emergency rations of online theatre to crisis-hit audiences; archive recordings, online monologues, and livestreams of works performed to empty auditoriums. But some people had mixed feelings about this onslaught of free digital theatre. As Emma Blackman told me, "Right at the beginning of lockdown, I read an article that said 'Why would I watch a reading of Hedda Gabler, instead of Tiger King on Netflix?' Theatre’s got crappy equipment compared to the monster that is Netflix. The performances that I engaged with online during lockdown were the ones that gave me agency as an audience member."

Blackman is admittedly a bit biased, as a producer currently working on forthcoming immersive show Forty Elephants. Her collaborator Amie Burns Walker explains that "in immersive theatre, we have a rule of thumb; if the audience wasn’t there, and the show could carry on, then it's not immersive".

"Plymouth Point" © Swamp Motel

"Plymouth Point" © Swamp Motel

In normal times, immersive theatre is a risk. It needs careful planning so that it can respond to unpredictable audience behaviour, and create a safe environment for exploration and play. But compared to the challenges facing conventional theatre producers, it’s starting to look pretty stable. Most West End theatres date from the 18th and 19th centuries. Even if you space out their auditoriums, social distancing is almost impossible in their labyrinthine backstage corridors. One of the only large venues to announce an Autumn season, Bridge Theatre, has opted for monologues by famous actors; they might shift tickets, but they won’t necessarily persuade new audiences that theatre is an artform that’s forward-looking, exciting – and worth saving.

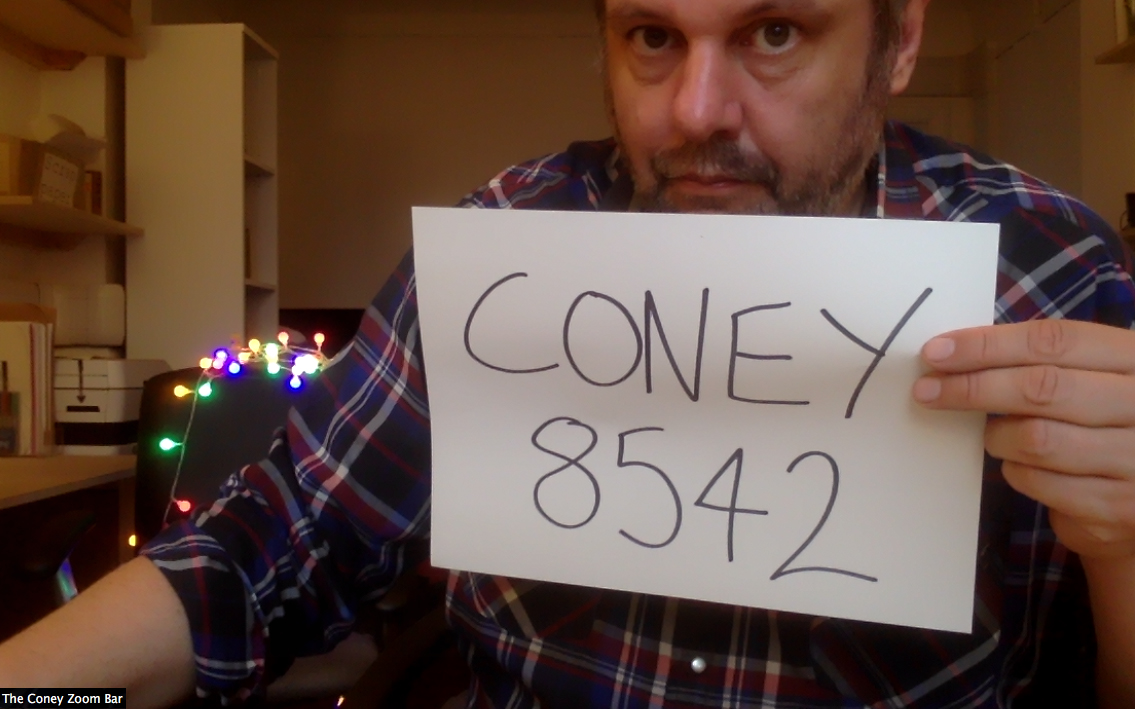

A Zoom game: "Plymouth Point" by Swamp Motel

Clem Garritty and Ollie Jones © Swamp Motel Swamp Motel’s "Plymouth Point" does. Its makers Clem Garritty and Ollie Jones are more used to making in-person immersive experiences; "There was a week or so where we panicked and didn't really know what to do", explains Jones. "But we were all suddenly using our laptops 500% more than usual – doing Zoom quizzes and chatting with friends – and we could see how boring that was gonna get."

Clem Garritty and Ollie Jones © Swamp Motel Swamp Motel’s "Plymouth Point" does. Its makers Clem Garritty and Ollie Jones are more used to making in-person immersive experiences; "There was a week or so where we panicked and didn't really know what to do", explains Jones. "But we were all suddenly using our laptops 500% more than usual – doing Zoom quizzes and chatting with friends – and we could see how boring that was gonna get."

"Plymouth Point" begins with a Zoom meeting with a distraught woman called Ivy; she explains that her neighbour is missing, and then sends the audience off to scour the internet for evidence of a murderous cult. As Garritty explains, "A lot of the platforms we were using were real, like Facebook and Google Maps. We thought, so long as we base it in all of this reality, we can go quite weird with the stuff we make up."

In a way it’s an inversion of the normal way that immersive theatre makers work. Companies like Punchdrunk are known for installing dazzling worlds in featureless warehouses. But Plymouth Point uses a rich landscape that’s already there, online – all it has to do is lead audiences through it.

Fusing communications technologies: "Telephone" by Coney

Another standout online performance of lockdown, "Telephone", builds its world using the audience’s own memories. Its creator Tassos Stevens uses the new-ish technology of Zoom to set up a human-powered telephone exchange, where people make faltering connections using old-school phone numbers. It quickly gains a life of its own, according to who’s in the room; "I feel I feel more like a passenger than an author," says Stevens. "One night, 'Telephone' ended in a lock in the bar until silly o'clock – we ended up sniffing marker pens."

It’s the latest experiment by Coney, an immersive theatre company who were better prepared than most to deal with lockdown conditions. As Stevens explains, "one of the ideas that Coney was founded on was the artist not being in the same room as the audience." Stevens wanted to work with a collaborator who lived 200 miles away, "but we didn't have the money to travel to each other. So we thought, why don’t we make something of the distance?"

"Telephone" by Coney, Screenshot: Tassos Stevens

"Telephone" by Coney, Screenshot: Tassos Stevens

"Telephone" filled a real need – one for connection, play, and social contact during isolation. But will that need ebb away, as socialising moves off Zoom and into the real world? "I still think there will be at least a niche audience", says Stevens. "It's amazing, the opportunities to be able to connect to audiences all over the world. But there's also there's a hyperlocal potential."

Theatre as a meeting point for communities

Afsana Begum’s Rightful Place Theatre company have just such a hyperlocal approach; their work "We Are Shadows" uses smartphones to take people on an audio journey down East London’s Brick Lane, and into the stories of women who’ve lived there for generations. It was made in collaboration with Coney and Tamasha last year, but is returning this Autumn - its approach feels newly vital after lockdown refocused audiences on their immediate community.

"We are Shadows" © Bettina Adela

"We are Shadows" © Bettina Adela

Rightful Place is predominantly made up of British Bangladeshi women from the London borough of Tower Hamlets, which was hard hit by Covid-19. Begum explains that "A lot of the community lives in extended families, so the impact has been huge, and there’s a lot of trauma that people are going through. These stories will need to be shared in some way." But she has to balance the needs of a group that’s desperate to reunite, with the challenges of connecting online; "We're an intergenerational group, and this is quite a deprived area. Technology is not always everybody's comfort zone."

The internet is often styled as democratic and accessible. But although online performances can connect audiences across the world, they risk missing out on representing communities that are closer to home. "There's a white male preponderance, in part because that’s true of tech and gamer communities as well," says Stevens, which is in part why Coney’s Network project shares expertise with other artists, from theatremakers like Rightful Place to the children who’ve participated in Young Coney projects.

Impossible challenge for theatremakers

The theatre that thrived under lockdown was able to straddle worlds – gaming, film, TV. But there’s a risk that the artists making these hybrid works will succumb to the pull of more lucrative genres, as theatre undergoes a painful few years. Elliot Hughes, of Hidden Track Theatre, spent lockdown making How to Win, a playfully political online game where each instalment was shaped by audience suggestions. He’s committed to getting back to making interactive in-person performances, whatever the next few years hold. But he warns that “It’s already very hard for working class artists to make it in this industry, and a lot of them are going to say: "However much passion I have, physically, financially, logistically, I just can’t keep going down this path."

Theatremakers are facing an impossible challenge. They’re being asked to be more innovative than ever, under the most unstable of conditions. Hughes says that "There are lots of little commissions from theatres who say: 'We don't know what happens next. Do you want to try something?' But the next stage is where artists will need slightly more money to take those ideas forward, and we’ll start seeing what kind of gambles theatres are willing to take, on work that audiences may or may not respond to."

It’s a biting observation. Donmar Warehouse was the first theatre to reopen, with unsettling installation Blindness, which used binaural sound and neon light to tell its pandemic narrative. But since then, established theatres across the UK are announcing pared-back seasons that combine experimental seating arrangements with traditional programming. After a tough few months, are audiences ready to step outside their comfort zone?

Safer than the traditional theatres

Theatre producer Brian Hook is buoyant about the potential of the next few months; “There’s this new zeitgeist where immersive theatre can come forward," he says. His company Hartshorn and Hook is reopening Great Gatsby for just 90 audience members a show - rather than the 240 of usual times – who’ll be able to spread out over the company’s lavish 1920s-style mansion set. The company will offer still more escapism with a new Doctor Who-themed experience next year. The economics of running two socially distanced shows are potentially punishing. But Hook seems unphased by the challenges; "We're not paying the kind of huge rent you’d get in a traditional theatre. And we keep food and beverage and merchandising revenues. So we’ve built a much safer, more stable model than traditional theatre."

Immersive "The Great Gatsby" with Jessica Hern © Helen Maybanks

Immersive "The Great Gatsby" with Jessica Hern © Helen Maybanks

As Hook acknowledges, though, there’s still a delicate balance to be struck. Drinks revenue helps keep the show afloat, but what if a tipsy audience forget about social distancing?

"Anybody who makes immersive theatre will tell you how important the airlock is", says Hook. The 'airlock' is the briefing that takes you from the ‘real world’ to the universe of the performance. It’s a concept that’s filtered into ordinary life, where bar staff issue prologues of safety advice before you reach your table. An Atlantic article introduced the concept of hygiene theatre; symbolic (and often ineffective) cleaning done in order to make people feel safe. Sometimes, you could imagine that we’re all living in a pandemic-themed immersive theatre show, where mists of disinfectant spray provide the atmosphere, and audiences perform elaborate dances of politeness around the toilet door.

Fear of the second lockdown

Although this bleach-scented pageantry endorses the government’s 'business as usual' agenda, the theatremakers I spoke to all feared of a second wave of Covid-19. Survival could mean sticking to safety rules – but breaking some artistic ones. Canadian thinker Marshall McLuhan argued that "the medium is the message"; but do form and content have the same inextricable relationship when you can’t be sure what forms will be legal in six month’s time? Stevens is currently looking at making interactive performances that can work both online and in-person. "What are the hybrids? Can a performance exist in both forms? Because we’re living with this uncertainty, where suddenly a city might lock down."

Back in March, it seemed conceivable that there might be one single answer to the question of when and how live theatre might return. Now, the landscape looks more uncertain. And it’s one where the safest investment isn’t traditional box office gold – it’s in forms of theatre that are flexible enough to adapt to whatever the future holds.

P.S. (from December 1st, 2020)

Since I wrote this article in August, the UK's theatre industry has suffered through an autumn of painful uncertainty, with localised closures followed by a national lockdown in November. Theatres in some areas – including London's West End – will reopen this week, but under tight social distancing restrictions, and the threat of further closures.

I feel a real sense of sadness that the UK government strongly encouraged theatres to put all their efforts into reopening their doors, instead of preparing them for a potential second wave by encouraging them to invest in online, outdoor and immersive performances. But I also feel encouraged by the growing sophistication of the experimental work that is being produced, and by the willingness of audiences and venues to expand their ideas of what theatre can be.

Alice Saville is the Editor of Exeunt, a UK-based online magazine covering theatre, dance and performance. She also contributes reviews and features to publications including Time Out and Financial Times.

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Übersetzung dieses Artikels.

Cooperation

This article ist from the book

Netztheater. Positionen | Praxis | Produktionen.

Published by Heinrich Böll Stiftung and nachtkritik.de in cooperation with Weltuebergang.net, editorial team: Sophie Diesselhorst, Christiane Hütter, Christian Rakow, Christian Römer. Berlin 2020.

You can order the printed book free of charge by writing an E-Mail to buchversand@boell.de

And here's the pdf.

Für Horizonterweiterung

Der Blick über den eigenen Tellerrand hinaus ist uns wichtig. Wir möchten auch in Zukunft über relevante Entwicklungen und Ereignisse in anderen Ländern schreiben. Unterstützen Sie unsere internationale Theaterberichterstattung.

meldungen >

- 17. April 2024 Autor und Regisseur René Pollesch in Berlin beigesetzt

- 17. April 2024 London: Die Sieger der Olivier Awards 2024

- 17. April 2024 Dresden: Mäzen Bernhard von Loeffelholz verstorben

- 15. April 2024 Würzburg: Intendant Markus Trabusch geht

- 15. April 2024 Französischer Kulturorden für Elfriede Jelinek

- 13. April 2024 Braunschweig: LOT-Theater stellt Betrieb ein

- 13. April 2024 Theater Hagen: Neuer Intendant ernannt

- 12. April 2024 Landesbühnentage 2024 erstmals dezentral

neueste kommentare >